Clean Code Tips for Scientists #1 - Reproducible Environments

Is your code reproducible? When you share your code with others, how can you make sure they obtain the same results as you?

Author commentary: I am starting a "clean code" blog series with simple tips that you can integrate into your workflow. I often write long, complicated articles that try to teach a lot at once. This is an attempt to chop things up in bite-sized chunks. Note that the Clean Code books by Robert Martin are great, you should read them if you have time! If not, you can follow these short articles :)

If you've written a lot of scripts and shared some of those scripts with colleagues or others, then you probably encountered the problem that the code doesn't always work on their device, or produces different results. When this happens, people may quickly lose trust in your results and begin to ignore your work entirely. So making code reproducible is extremely important! Even if you are a scientist and not a professional software developer. I'll explain a simple strategy you can take to make your code more reproducible.

Code Environments

First we must take a small step back from your code. Because when you write your script, it is not standalone. It exists in a certain "environment". Besides the hardware of your computer and your operating system, this involves your programming language version and all the (open-source) packages you used to run your code.

When sharing the environment with someone else, you do not want to give them your computer, right? Nor do you want to send all the dependent package code on your computer, because that can easily become gigabytes of packages and dependencies. The environment may not even work exactly on their computer. All kinds of issues may make relocating the environment difficult, for example if they use a different operating system (Linux instead of Windows).

Instead, you want to share a way to install an exact copy of your environment, by sharing the exact configuration of packages you used.

Python Environments

In Python you typically share your dependencies with a requirements.txt file. You can find plenty of blog posts online about this approach, like here. There are also alternatives like Poetry that try to make Python environment management easier for you.

I won't go into the details of Python environments here, but please know it's possible. Instead I'd like to show how this problem is tackled in the Julia language. If you prefer another language, then you can consider this an example.

Julia Environments

In Julia everything can be done with the built-in package manager.

Let's say you have your very important script file. It looks something like:

using DataFrames, LinearAlgebra

# much important code for your colleagues

What you want to share is the exact same versions of the packages you are using to run this script, including all the package dependencies (for example DataFrames v1.5 is using DataAPI v1.14 under the hood). If you can easily send that knowledge to your colleague, then you can be sure they will get the same results.

Start with an empty environment. Add all the packages you use for your script. You can use the Julia Pkg mode on the REPL with ], or write something like this:

using Pkg

Pkg.activate("ExperimentNinetyFive")

Pkg.add(["DataFrames", "LinearAlgebra"])

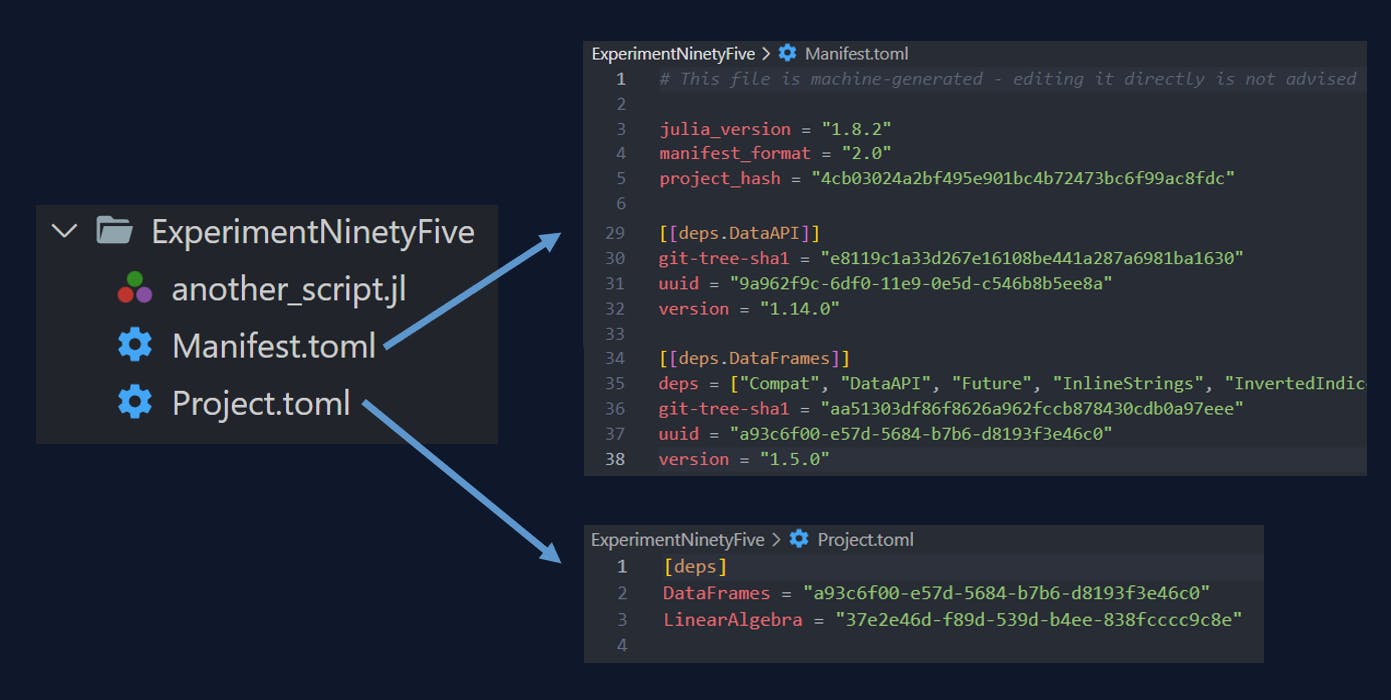

You will now have a folder called ExperimentNinetyFive on your device, with two files inside: a Project.toml and a Manifest.toml. The Project.toml simply lists the packages. The Manifest.toml is what describes your exact environment:

The Julia version

All packages you added with their version, such as DataFrames version 1.5.0

For each package: lists all their dependent packages. Such as DataAPI for DataFrames.

For each dependent package it specifies the version, such as version 1.14.0 for the DataAPI package.

Here's a picture showing a snippet of the Manifest.toml (it's 234 lines in total for me):

To share a reproducible environment with a colleague, all you need to do is put the script inside the same folder, and then zip it, or push it to a repository, or whatever way you prefer, and send it to your colleague. After receiving your code, all your colleague now needs to do is this:

using Pkg

cd("path/to/ExperimentNinetyFive")

Pkg.activate(".")

Pkg.instantiate()

# and then they can run the script

include("another_script.jl")

The function Pkg.instantiate will install all the packages exactly according to the Manifest.toml. So your colleague will use the exact same versions as you did.

That's it! Modern programming languages come with a simple package manager for the purpose of sharing reproducible code.

If your code is meant to be re-used inside other people's code, the next step would be to make a package that can be installed and updated automatically (instead of emailing your script). Packages are essentially installable code, including a reproducible environment and preferably things like documentation and tests. But that's for another blog post.

In general: never only share your code. Share a reproducible way to setup your coding environment as well!

Appendix

Warning: You inherit the global shared environment!

What do I mean with this? Let me briefly explain. When you start a Julia REPL you typically start in the global environment like @v1.8. If you install packages in @v1.8 and then switch to another environment, those packages are still available. This means you may accidentally forget to add those packages to your new environment, because your script just works. But the the environment you share with the Manifest.toml is still not reproducible for someone else! It's missing some dependencies.

To avoid this problem, and other issues, I typically keep my global environment as clean as possible, with only a few utility packages that I only use on the REPL, such as Revise and OhMyREPL and LocalRegistry. This way I keep all my environments separate.

Similarly be careful when switching environments within a single Julia REPL session. I would advise to test your script once in a fresh REPL, before you send it to others.

Pluto does it all

Pluto notebooks are designed to be reproducible. Under the hood they contain the package environment inside them (check by viewing the Pluto .jl files in your favorite text editor). This can make it easier to share a Pluto notebook instead of a script or package.

Other programming languages probably have other solutions for easy sharing of environments and scripts (though Jupyter notebooks do not do this well). Or you can try online editors like Replit, which maintain the environment for you. I would still advise to understand how package environments work in your favorite programming language, because you cannot use notebooks for everything. And leaky abstractions are always a good reason to occasionally look under the hood.