How to solve the two language problem?

An overview of software technologies to get speed and simplicity at once. Comparing Python, C++, Cython, Numba, Julia and more.

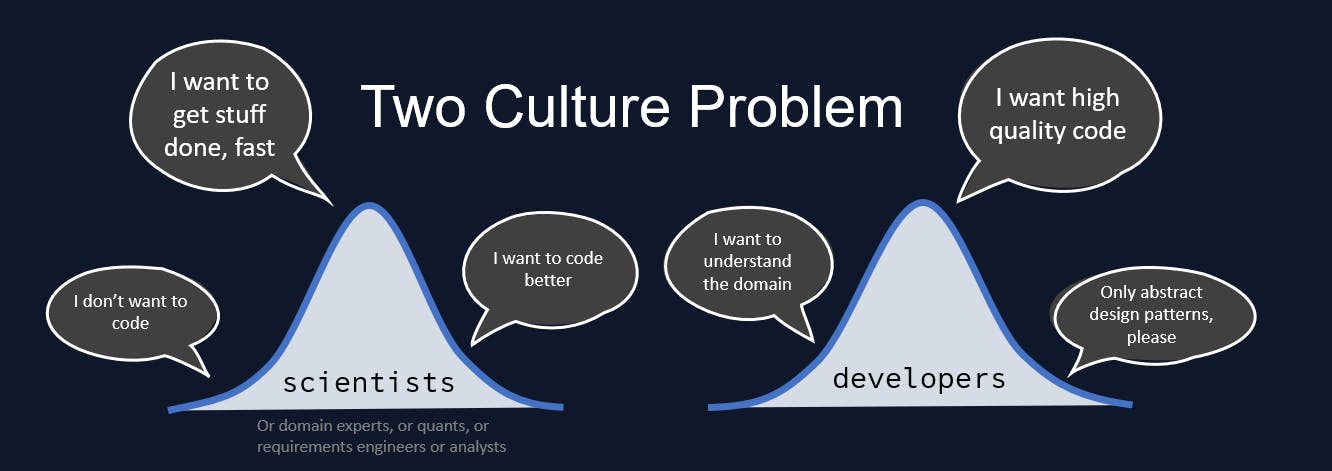

My professional obsession is solving the Two Culture Problem. How can scientists optimally join forces with software engineers and their principles, so that we can work on the same problems together? How to accelerate the cycle from idea to product? The Two Culture Problem requires a solution to the related Two Language Problem, which has a technical nature. A solution to the technical problem does not guarantee a solution to the organizational problem, but when it comes to engineering cultures you first need to prove the technical solution before you can even begin to tackle the social implications. I have a strong opinion on the best technical solution, but let's review all our options.

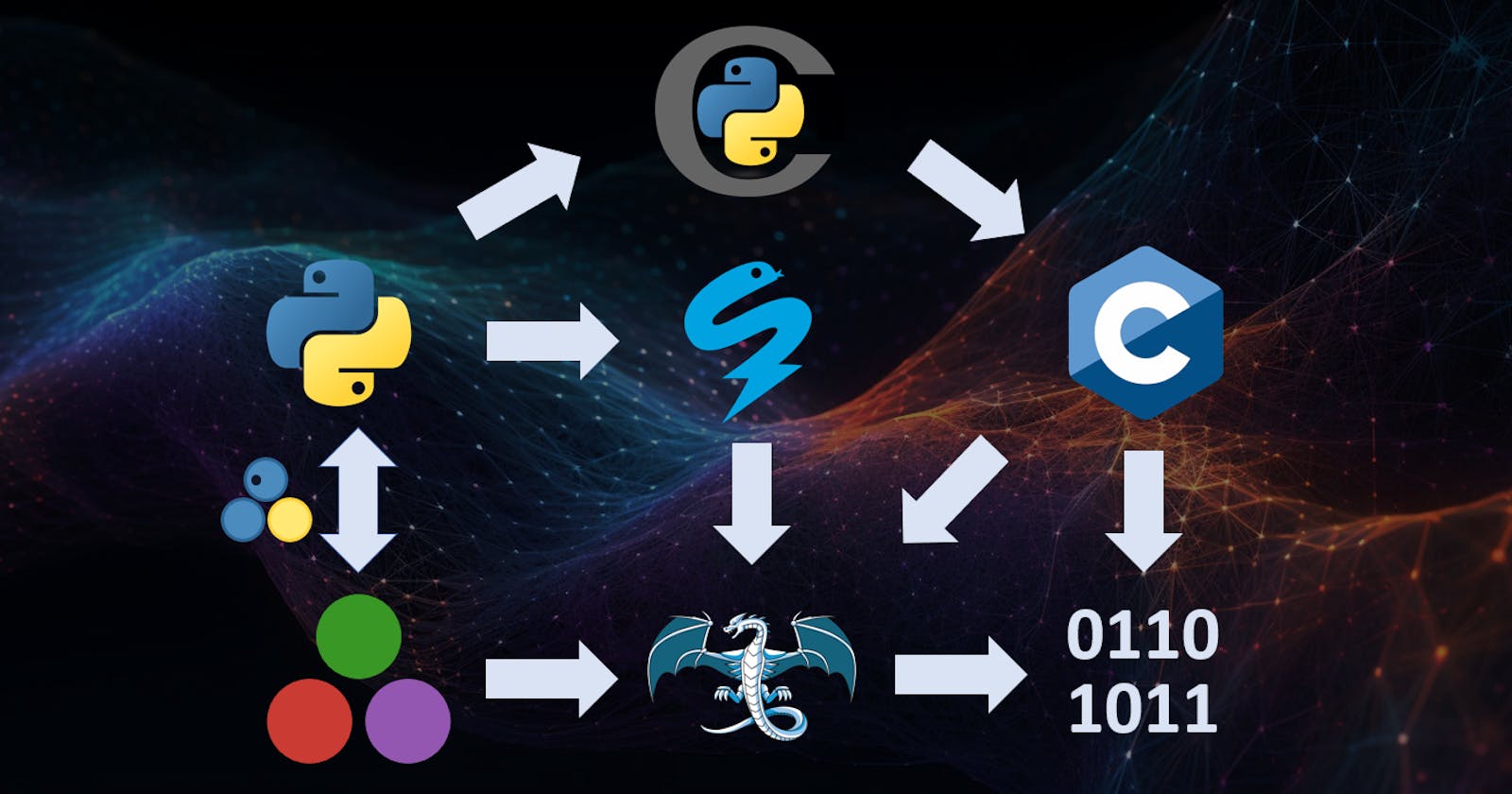

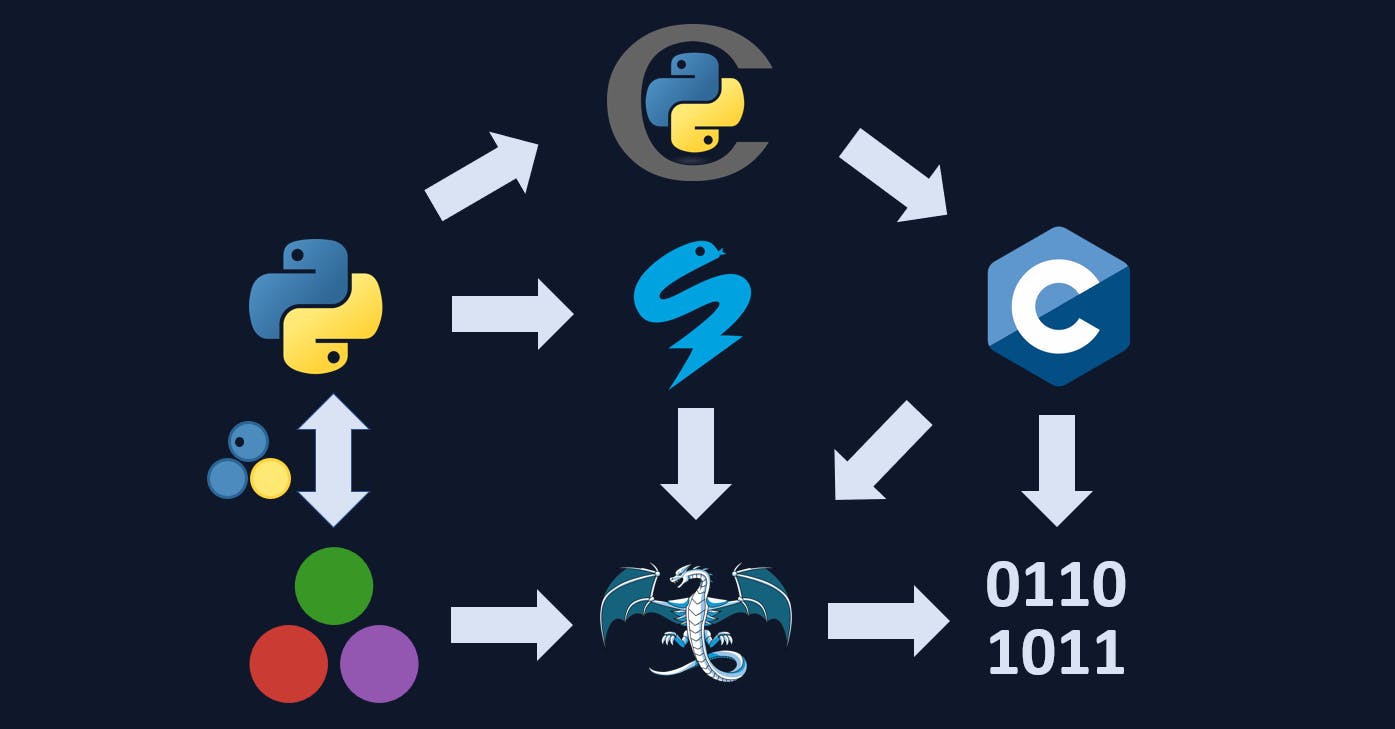

As far as I can tell, we have the following alternatives:

Accept the status quo: use a slow and a fast (usually harder) language

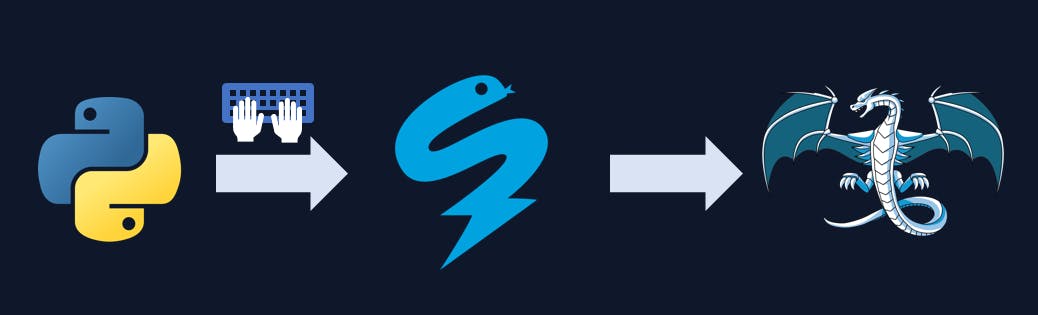

Code generation using a look-a-like framework inside the slow language

Using (LLVM-based) optimization frameworks that look like the slow language

Speed up the slow language itself, working around its limitations

Design a new language that is both easy and fast

There are many tutorials about all of these options. Here I'd like to write a short overview of all of these.

For another similar technical overview, see Martin Maas's blog posts about Julia vs Python vs Numba vs Cython.

The two language problem - Python and C++ as a primary example

Your scientists or domain experts write prototypes in a simple language, let's say Python, where they can rapidly explore, do dynamic data analysis, model desired behavior and gather requirements from users. When they find something valuable, software engineers convert the prototype into high-performant code, let's say C++, and integrate it into production systems to sell as professional services to those users. This is my assumption of the status quo.

(I will continue to refer to the modeling culture as "scientists" whether or not they are actual scientists, domain experts, requirements engineers, data analysts, quants or any other kind of expert whose primary job is modeling the behavior of your product without actually writing and deploying the final source code.)

Depending on the size of your organization and the skill level of your engineers, you may end up with several configurations:

Teams of highly skilled scientific engineers who can do all the work

Teams with a mix of scientists and software engineers

Separate teams of scientists and separate teams of software engineers

You may have any combination of the above. The first option is a team of unicorns, which I have seen the least, but is amazing to work with.

Perhaps you have accepted this status quo. As the organization grows, separate code bases may evolve for the two types of tasks. In my experience, the production code rarely gets re-integrated into the analysis code, because it's not worth the effort in the short term. Long term you may get inconsistencies and other issues, but that's typically for someone else to worry about. Or perhaps people notice the problems, but profit margins are good, so why worry?

If you integrate your fast code (C++) as embedded libraries into the slow language (Python), you typically need some intermediate glue code or language in between. This requires yet more technical expertise from your people. See for example this blog about How to Call C++ from Python.

One stated benefit of keeping the two-language culture intact is that your prototypes and your scientists never mess up your production systems. The production systems are brittle and valuable, so this is a valid concern, but I think there are better ways to teach people to write better code than by blocking them.

For this article, I assume you are looking for alternatives. Maybe the problems have grown too big, or you want to avoid them early on, or you simply cannot hire enough senior software engineers. Thus for one reason or another, you need your scientists to be deeply involved in the software development.

Learning C/C++ is still a good idea to grow your expertise or the competence of your scientists, but it can take a long time to develop. At a minimum, I advise learning what it means to compile and link libraries. And learn a bit about computers by reading great summaries such as What Scientists Should Know About Hardware to Write Fast Code.

Still want to find a technology that's easier to use, yet brings some of the hardcore software benefits? Let's see what's possible!

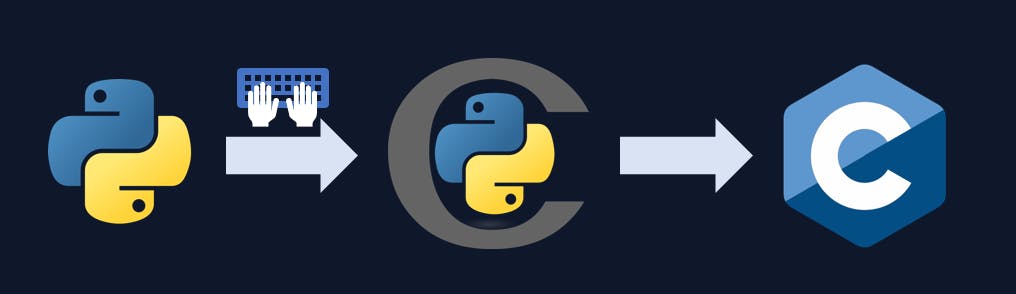

Code generation - Cython example

Generating low-level code, most likely C, from a high-level language, most likely Python, is typically done to try to avoid some of the disadvantages of the two-language problem. Maybe you want to compile static libraries to embed into devices. Or you have some other reason. Unless your examples are very simple, do not expect big performance boosts though, the generated code still needs to make similar kinds of assumptions as the high-level language. Also, most code generators do not support the complete language semantics, so you will have to make sure your high-level code adheres to the capabilities of the generator.

In Python you can use the Cython 'compiler' to help you generate C code. On the surface it looks a lot like Python, yet with C types and certain decorators. This means you need to rewrite the parts of your codebase that you want to speed up. The process of turning Python into Cython is sometimes called "cythonizing". You get such examples in the Cython quickstart tutorial:

@cython.cfunc

@cython.exceptval(-2, check=True)

def f(x: cython.double) -> cython.double:

return x ** 2 - x

def integrate_f(a: cython.double, b: cython.double, N: cython.int):

i: cython.int

s: cython.double

dx: cython.double

s = 0

dx = (b - a) / N

for i in range(N):

s += f(a + i * dx)

return s * dx

You have to build this cythonized code. As I mentioned, this happens in two stages:

The

.pyor.pyxfile is converted by Cython to a.cfile.The

.cfile is compiled by a C compiler to a.sofile (or.pydon Windows) which can beimport-ed back into Python with setuptools.

The downside of Cython, and any similar C code generator, is that you obtain rather obscure C code. If you want code obfuscation, you can consider that a benefit, but trouble begins when you have to work with that C code. It can be hard to debug once deployed in the field. Make sure to add lots of clear error messages and logging. If you integrate the generated code inside existing C/C++ codebases, your software engineers may dislike writing the necessary glue-code (I learned that from experience). Finally, naive Cython is not very performant and writing optimized Cython can be as difficult as writing regular C code. But the benefit is that you can move gradually up in complexity.

How to make a standalone-ish distribution? Cython generates code that interfaces with the python runtime. You can create a binary executable, but you also need to distribute it with libpython.so which is the python runtime. Moreover, you also need to add all the python dependencies and .so/.dlls that those packages are using. This might be a bit tedious using Cython, but it is certainly possible. Other packages like Nuitka make this process a bit less painless by figuring out all your dependencies.

Fun fact: Code generation is sometimes referred to as "transpiling", since you translate your code to another language that's ready for compiling.

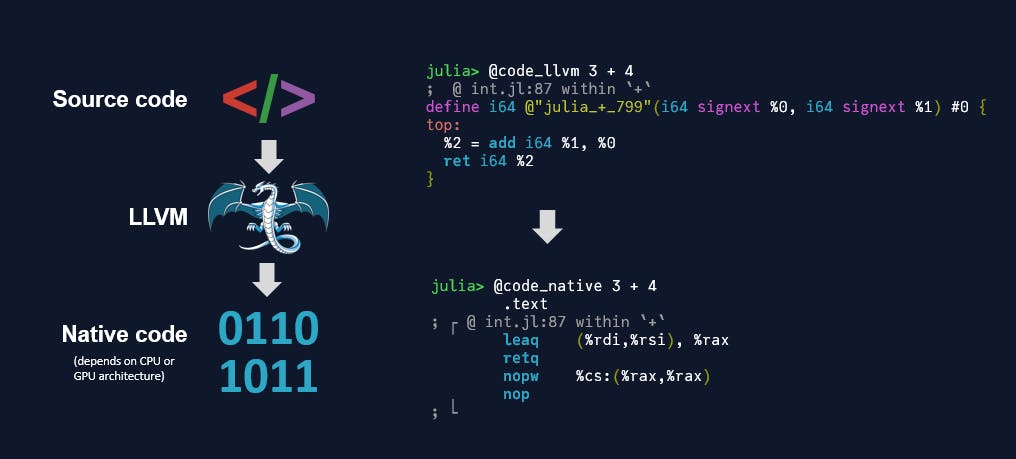

Interlude: LLVM

What if we do not want to write or generate C code? Do we have any other options? Yes, we can generate something else: LLVM code! Before we go into such frameworks, let's do a quick introduction into LLVM itself.

LLVM is a middleman between your source code and the compiled native code. Compilers typically consist of two stages: byte code and native code. The byte code is an intermediate representation that is agnostic of the CPU or GPU architecture. LLVM is an attempt to standardize the byte code definition, which will then be compiled for you to any architecture you want. In some frameworks or languages (like Julia) you can ask to see the LLVM code, and the eventual native code, the processor instructions, which is typically assembly code (that's just before it becomes those zeros and ones you always hear about).

Frameworks that use LLVM may store the compiled native code in memory. In that case, if you want to distribute the compiled code, you need the option to package the native code into a library (that's a .so on Linux or a .dll on Windows) together with all of its dependencies. This packaging option may be important to investigate for your deployment strategy.

Fun fact: the clang compiler from C also compiles via LLVM. So if you write Cython and then compile via clang, you are taking an interesting route.

Optimization Frameworks - Numba example

Numba is an LLVM code generator that integrates directly with Python. What you need to do is add decorators to every Python function you want to optimize. In principle it looks simple:

@jit(int32(int32, int32), nopython=True)

def f(x, y):

return x + y

JIT stands for Just-In-Time, as it compiles to LLVM at the moment of calling the function, and inferring which types you used, just in time before executing. You can optionally provide the types yourself, as I did above. And there are lots of other settings for the @jit decorator, like the nopython mode to get faster performance.

Only a subset of Python is supported with Numba. It works well with your NumPy code, they made sure of that. It doesn't work with other packages such as Pandas, because those work differently. Even dictionaries are not supported by Numba. Nobody writes a custom file format parser in Numba, it's purely for numerical code.

If you want to compile to GPU: there are other decorators, such as cuda.@jit. This suggests you need to edit your code for GPU.

If you want to compile ahead of time, you will again have to replace all your @jit decorators with the @cc.export decorator and be explicit about your types.

You cannot debug the jitted Numba code itself, you'll have to change the decorator setting to debug mode and use the gdb tool, so be careful there. That's another disadvantage of Numba.

We have never tried to make a standalone distribution of Numba compiled code, but I assume you ship the entire Python environment, with the ahead-of-time compiled code. If someone has experience with the nitty-gritty details of distributing Numba code, then let me know!

Codon

Codon is a recent attempt similar to Numba, except it claims zero-overhead; you do not necessarily have to decorate your code. Well, except if you want to use it inside larger Python codebases (you probably do), then you have the @codon.jit decorator and other decorators depending on your use-case.

Codon has only 9 contributors at the moment, and it has a non-permissive license, so you'll have to pay to use Codon commercially in production. It's interesting but looks more like a startup than a regular open-source project. Similar to Numba it only supports a subset of the Python language, which may get better over time (or worse, if Python evolves, yet the developers do not update Codon).

Jax, TensorFlow, PyTorch

Every scientific computing and machine learning framework in Python implements its own optimized numerical libraries it seems. Some of them, like JAX, have a @jit decorator like Numba. All these frameworks look like Python, but to get performant code you'll have to use their API, not Python itself. Often you write Python in a more complicated directed-acyclic-graph (DAG) structure that can be fed to the underlying libraries for execution. Don't ask me how to debug these things. Please consider whether you are really writing Python or another language.

Also see this section from the Mojo language comparing such Python improvements.

Boost the slow language - PyPy

There is a continuous effort to improve the performance of slow interpreted languages like Python and R. In a blog post called Python 3.14 Will be Faster than C++ the author joked that linear extrapolation of Python improvements will soon surpass C++ performance. Let's see how that graph evolves in the next Python versions.

PyPy

An alternative to waiting for Python to improve is PyPy. This is a replacement for CPython. Note, CPython is not Cython. CPython is essentially Python itself, as the Python interpreter is written in the C language. PyPy is an attempt to make the entire Python language faster with a better interpreter. PyPy can optionally use LLVM as a backend, to use similar tricks as Numba, and also has a JIT decorator.

In general, the Python language design creates limitations on the performance, see this video for example on How Python was Shaped by Leaky Internals. If you don't want to change language, you may hope that Python 4 ever comes around with syntax that can actually be optimized.

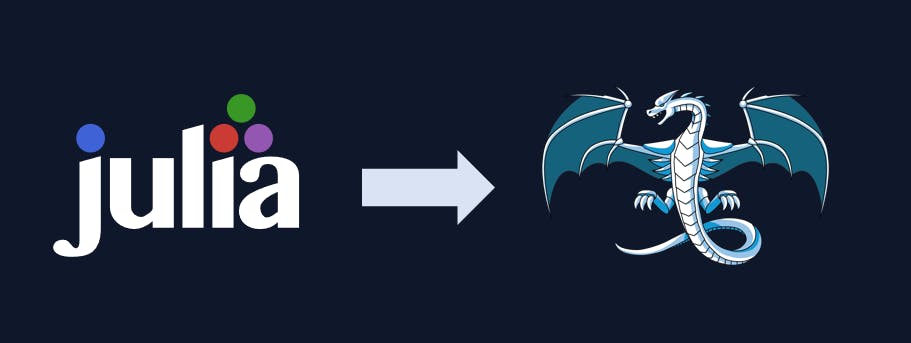

An optimized language - Julia as example

If you don't want to wait for Python 4, then there's Julia instead. Julia is a language that is optimized for talking to LLVM, while looking as similar as possible to high-level languages like Python and MATLAB. In short, it's an LLVM whisperer. This makes it fast and easy. See Why Was Julia created? to get an impression of the rationale.

Similar to Cython and Numba, you can optionally add type information to Julia, which can help the compiler, though Julia is good at type interference.

function f(x::Int, y::Int)

return x + y

end

Is Julia better than Numba and Cython? For an opinionated and long blog post read Why Numba and Cython are not substitutes for Julia. There are also lengthy discussions in this discourse on Why weren't Numpy, Numba, SciPy good enough?. And I also like Martin Maas's blog post about Julia vs Numba and Cython.

I would summarize the benefits as: You don't have to decorate your code, Julia is the JIT decorator. You can write the same code for CPU and GPU. When compiling ahead-of-time, it's again the same code. The compiler can optimize across all Julia code, not just a single package like NumPy that you are currently using. Composability is often praised: Julia packages work easily together.

The downside of Julia, if you are coming from another language like Python, is obviously that you have to learn another language. Though I wonder how much more difficult Julia is compared to learning a complex framework like Numba. And writing optimized Cython can be considered similar to writing another language. Julia has many similarities with Python, check for example this cheat sheet to compare MATLAB to Python to Julia, except Julia bypasses the problems that make Python difficult to compile to LLVM.

Similar to Cython and Numba, naive Julia code is good, but not necessarily as performant as optimized C. Read the performance tips to get the most out of your code.

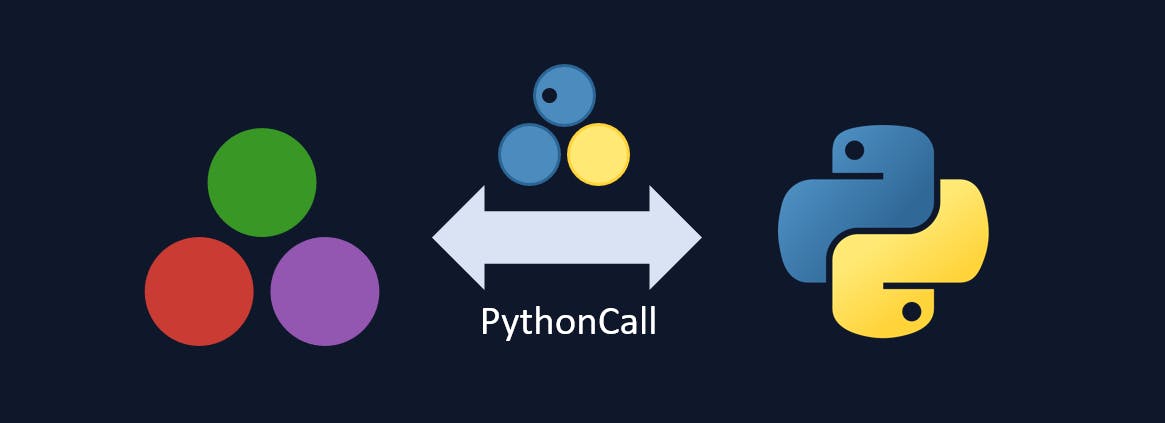

If you want to move gradually to Julia, you can embed Julia into Python via PyJulia or the more recent two-way package PythonCall. Or you can re-use existing Python code inside Julia, via PyCall.jl, or the aforementioned PythonCall. This way you can use Julia as if it's yet another Python framework, instead of a completely new language. You can even send Pandas dataframes to Julia and back.

Similar to Numba, Julia stores the compiled native code in memory. In the upcoming Julia 1.9 release, this code will also be automatically cached on disk per Julia package, so compilation happens only once, instead of the first call in every new Julia session. Ahead-of-time compilation was always possible with PackageCompiler.jl. The PackageCompiler is not actually compiling (Julia and LLVM do that), it simply gathers the in-memory compiled code and stores it in a .so library (or .dll on windows). This can be used for a standalone library of your compiled code, and will automatically include all dependent libraries. I have written a long tutorial on how to embed such Julia libraries inside C++ on my private website.

Static compilation of Julia, into tiny libraries fully independent of the runtime, is in an early stage with StaticCompiler.jl and StaticTools.jl, but needs more investment. Once you try out static compilation, you will notice that it enforces limitations on your code, because you cannot use all the fancy dynamic language features. I believe this is an unavoidable trade-off in any of the discussed technologies so far, but I'd love to be surprised on this point.

Other attempts to make a fast language easier to use are Zig, Swift and GoLang to a certain extent. Rust is very interesting, but I would not call it easy for scientists. None of them are targeting numerical computing as much as Julia.

Mojo

A new language that was revealed very recently is Mojo. In their article Why Mojo? they rephrase the two language problem as a Two World Problem, or even three world problem (Python, C++ and CUDA) for machine learning. From the code snippets on their website it looks like they want a Python compatible language that has features of Rust. Note that Mojo is not yet released to the public, the mojo github repository is empty at this time of writing, so we don't even know if Mojo will have a permissive license. Ambitious, but very young. We'll keep an eye on this one.

Final Comparison

What are good comparison criteria? I have chosen a few below. The development community size can be used as an estimate of how much effort goes into each project. Other than that I have tried to compare the usage and technology choices. I don't want to give quantitative performance comparisons here, they are heavily dependent on your use case, but from the benchmarks on complex examples that I have seen, Julia typically performs best. However, performance might not be your main criterion. Other unlisted aspects, such as debugging, profiling or cloud deployment may be more relevant for your use case.

| Cython | Numba | Julia | |

| Contributors | 430 | 298 | 1386 |

| Github stars | 7.9k | 8.6k | 42.2k |

| Backend tech | C transpiler | LLVM | LLVM |

| Usage | Decorators and Cython types | Decorators everywhere | Learn another language |

| Python interoperability | Import cythonized modules | Just-in-Time (JIT) decorators | PythonCall package |

| Performance | Decent | Good | Best |

| Distribution | Ship the .so with all dependencies | Ahead-of-Time compilation decorators | Ahead-of-Time compilation via PackageCompiler.jl |

While I have a preference for Julia, I tried to stay as unbiased as possible in this blog post. All options are amazing open source projects and are maintained by mostly voluntary developer communities. Investigating them all is a humbling experience in the complexity of software technology.

There are other software engineering requirements that I have not yet included in this post, but might be important for your use case:

Package management. How easy is it to create and install a package, with all of its dependencies, in the chosen technology. I believe Julia's Pkg is superior here.

How does dependency management and distribution of binary artifacts work exactly? These nitty-gritty details can slow down your project. I have not yet tried this extensively for Numba. Cython involves some manual work. Julia has an artifact manager that works together with the package manager inside PackageCompiler.

Complex cases, like multi-threading inside the framework or external threads calling from another language. (Note: Julia doesn't have the global interpreter lock (GIL) like Python. Cython can release the GIL in certain cases.) I haven't gone into such topics yet, but there are many complex use cases that you may want to gradually add to your codebase. How far can you go with each technology before hitting a wall?

Finally, remember that a technical solution does not necessarily result in a cultural improvement. If you hired a lot of scientists or analysts or domain experts, and none of them have the necessary software skillset, it is difficult to improve collaboration with software engineers by forcing a 'better' technology onto them. You will have to empower your scientists to learn the necessary software development tools and processes, such as version control, test-driven development and continuous integration. Vice versa, your software engineers can learn the business domain and the tricks of numerical computing with the help of your scientists, to know exactly what code to write. By bridging these gaps, you can create a more effective team that can leverage the full potential of the technology investments you make.

Thanks to Jorge Vieyra and Jeroen van der Meer for reviewing and suggesting excellent improvements to the article.

These long posts take me quite some time and effort to write. If you like them, please encourage me by leaving a comment with suggestions or subscribe to my newsletter. With enough support, I intend to write a book about building and deploying professional numerical computing applications. With Julia examples.