How to deploy algorithms anywhere?

Important elements to examine when transitioning code to a production environment

Let's say you are an incredible scientific programmer. You've got some pretty math, machine learning model or scientific computing code. And you want to give it to other users. Maybe even turn it into a real product and make a profit from your work. How do you "deploy" that piece of code? Most scientists do not think much about this problem at all, but it can have a great influence on how you should develop your code.

Basically, we need to take what you developed, turn it into something which can be given to the user, so they can install and use it in their computing environment. What to provide depends entirely on the environment of the user. So you'll first need to understand that: the so called "production environment", the environment in which your "product" or service will operate.

The easiest way to make sure the code works, is to write the code inside the production environment and run it there. Boom! Everything works. Some startups operate like that, but it's not very common. It's quite a risk to mess up your production environment accidentally. It's also possible you have no direct access to your production environment, for example if you are writing code that needs to be installed on millions of cars around the planet.

If you want to know about the possible deployment processes adopted by many possible companies, I recommend the Pragmatic Engineer - Shipping to Production. Unfortunately, that focuses mainly on procedures and assumes quite some software knowledge already.

I think there's roughly three options here that we need to consider:

You fully understand and control the production environment. For example, if you work for a car manufacturer and you write the firmware, then you deploy the code into an environment that you control (or at least your employer does). You might be able to prepare the production environment to best suit your chosen algorithm technology.

You understand the production environment, but you do not control it. In the previous example, let's say you are a vendor selling software to the car manufacturer. You probably need to restrict yourself to the production environment of your customer.

You neither know the production environment, nor do you control it. Let's say you are selling software that might run on any laptop with any operating system (MacOs, Linux, Windows), or even on mobile devices. You have no clue what to expect. This can be tough, but is quite common for consumer software.

In the latter option, the modern era has tried to work around the issue by deploying to servers (or "clouds"). In that case you fully control and understand the production environment, and you merely provide the user with access to your service. This does assume your user has internet access, which seems reasonable these days, but is not true in environments like super-secure semiconductor factories (where I may have some experience).

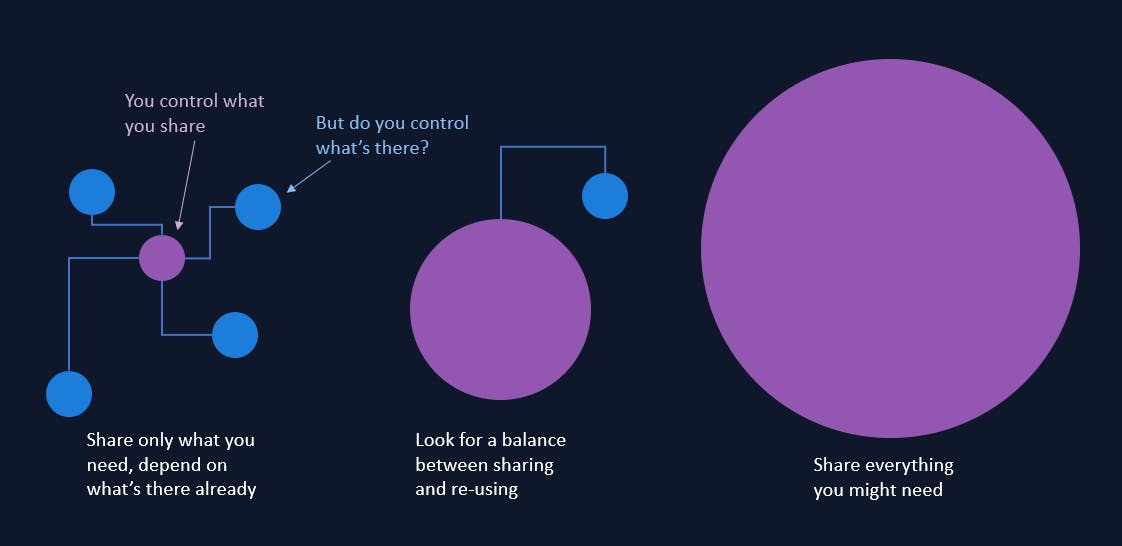

Assuming you understand your production environment, you are still looking for a balance between how much you share yourself and how much you re-use. If you can re-use software components in the production environment, you can distribute a smaller deployment package/artifact. But you may have to conform to things you do not control, which can be unpleasant.

Let's move on to typical deployment options. What is this "thing", this "artifact", that we send to the production environment? Here's the general options I work with:

Deploy the raw source code files and make sure the interpreter/compiler is available in the production environment. Python and Java typically work like this.

Compile the source code to something "standalone". More C and Rust style.

Package everything together and ship it. Docker containers are the most extreme version of this approach, as they include even the operating system.

But there are plenty of options in between, including all combinations of possible production environments and their restrictions. Some combinations are not possible, for example when deploying on an Arduino you are severely limited by computational capabilities and you will probably have to compile a tiny standalone solution. If you've just written some massive Python AI monstrosity, you'll have to rewrite it to something much leaner. That can be very painful to find out at the end of your project.

That's why it's important to have some end-product in mind and work backwards from that vision in your development. Scientists and business people like to keep the behavior of the software in mind, what the software will do and such, but forget about where it will operate.

Source code deployment examples with Julia

The Julia language is currently my favorite language, as it tries to unite multiple programming worlds; those in science and in software engineering. It focuses on being easy to use and fast to execute. In theory Julia can be deployed anywhere, but being developed primarily by numerical computing professionals, it lacks some ease of use in that deployment area. I think that highlights some of the blind spots of typical scientists. I'll use Julia, and it's pain points, to highlight deployment considerations, while trying to keep everything generic to other languages.

The most basic deployment happens when you, as a developer, begin your journey into the programming language. You install the language, you type some code in some editor (or directly on the REPL), and you run the code. That's it. Note that when you installed the language, you use the deployment mechanism from someone else.

The second most basic deployment, is to give your code to a fellow developer. That developer will understand their own environment (to a certain extent). They probably have already installed the programming language. If not, they can follow the same installation instructions.

Now if the code you write depends only on the installed language, everything should work. But in the modern era, you typically depend on plenty of other people's code. You'll be importing open-source packages left and right. That's really nice, since it saves you a lot of effort. But now you need to share those extra packages with your fellow developer. Note that packages may include pure source code, but also compiled libraries.

You can either:

Create a "bundle" of all those open-source packages and share it, or...

Share a reproducible way to install all that code. See my previous article on that.

So if you would like to share a piece of code with someone, you need to consider how to share everything that code depends on.

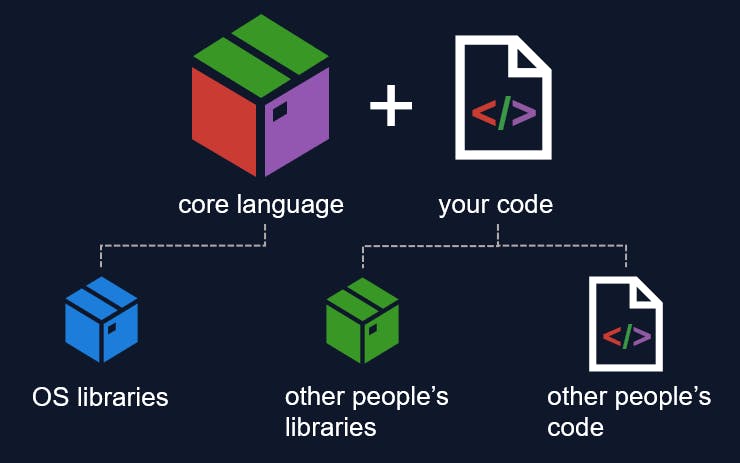

These scenarios I described so far are simple (installing for yourself or sharing with a colleague), but they already show the concepts we have to take into consideration when sharing:

The core language features.

The default operating system (OS) libraries which the language depends on.

The code you wrote.

The code others wrote for you.

Any libraries created by others.

You can choose which parts you share directly, and which parts you allow to be installed/downloaded.

For installing source code, Julia depends on the package manager to install everything for you, by downloading it from the internet. This all runs with an existing Julia installation. However, Julia doesn't have a good source code "bundler", where you quickly create an installer with your code in one "bundle" or "distributable" (for example an executable on Windows) and you give that to a person. I think that's missing in the Julia ecosystem.

Note that such solutions are operating system dependent. For Python, you've got py2exe for windows, py2app for MacOs, pex for Unix.

Compiling libraries

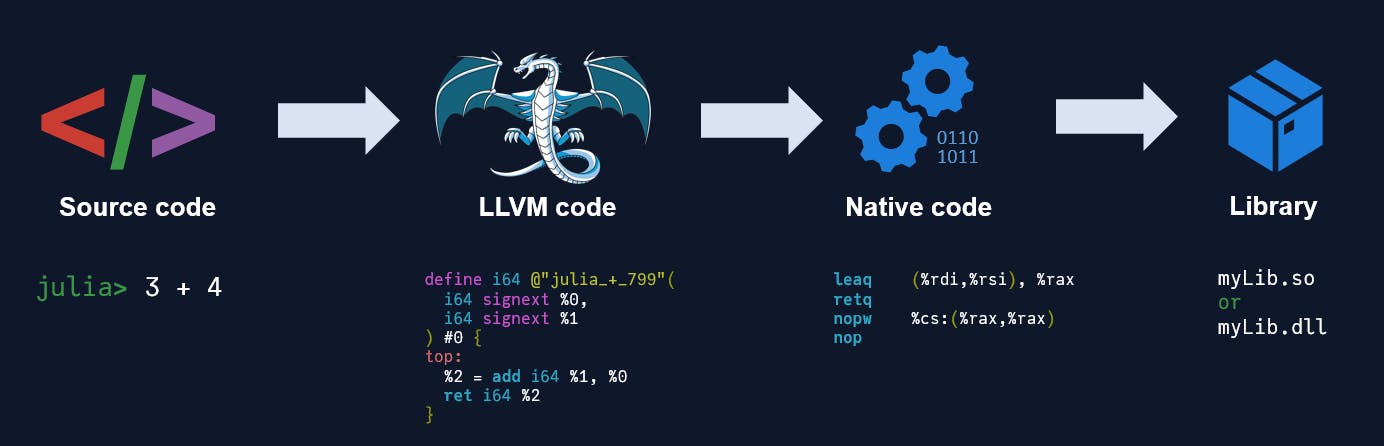

A computer doesn't directly execute your source code, it needs low-level instructions. Turning your source code into machine instructions is called "compiling". In my previous article How to Solve the Two Language Problem, I roughly explained how technologies like Julia work. There are lots of steps, but on a high-level, you go from 1) written characters to 2) an LLVM representation to 3) machine instructions, a.k.a. native code.

When you gather all that native code and place it in a library (.dll in Windows, .so on Unix), then you can share that library directly with an end-user. Assuming you know which operating system they are working on. This process of turning the machine instructions into a distributable library is often considered part of the compilation process.

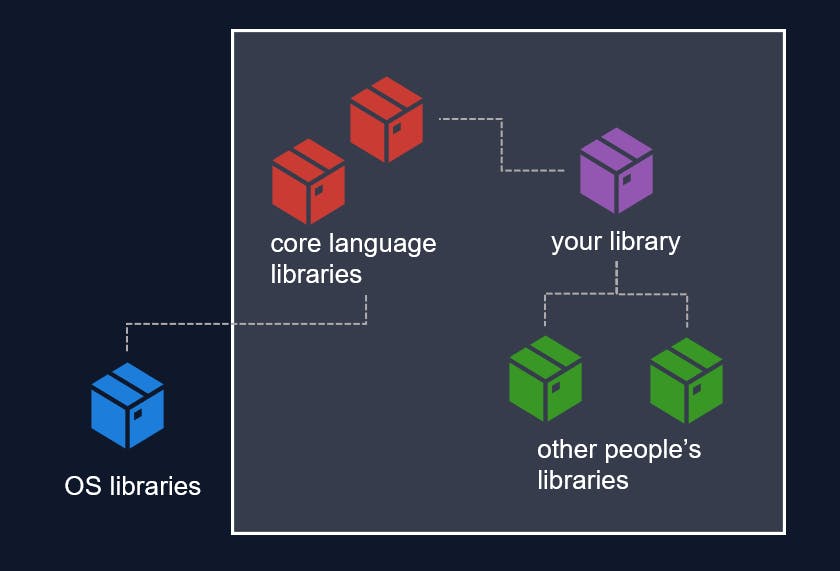

And you will still have to "bundle" any external libraries together with your compiled library. This may include certain libraries from your chosen language. Libraries can be linked statically or dynamically, but I don't want to go into those details here. I do want to make you aware, to always, ALWAYS, consider ALL your dependencies. If you forget to consider a dependency, and it's missing or mis-located in the production environment, your program will not run and your deployment has failed!

The Julia language community provides the PackageCompiler package. If you want to make everything fully standalone, you are looking at creating an "app". This will:

Compile your code, and the dependent code, into one library.

Gather all Julia language libraries.

Gather all dependent third-party libraries.

Place all of those together in a folder, and make sure the dependencies are linked correctly.

Optional: filter out unnecessary libraries (at your own risk).

Note that the default operating system libraries, such as libc, are not included in this "bundle" of libraries.

It's possible in Julia to remove as many dependencies as possible, to go to a very small distributable library, and even become independent of any core Julia language libraries. For example, you can run Julia on an Arduino. But it's far from trivial. Keep your eyes on StaticTools.jl to follow the developments.

Languages like Rust are geared fully towards statically compiling and deploying small independent libraries. That results in very good tooling for the library deployment use-case.

Docker: just deploy everything

Docker tries to be the software technology to solve all deployment. It wraps everything you need into a "container": code, runtime, system tools, system libraries and settings. It's all about portability: to make sure you can share your software with others, as standalone as possible. I won't go into details, Docker has solid documentation.

You will still need to install Docker itself in the production environment. This means that if you do not control the environment, you may never be able to run Docker containers there.

You will have to decide how to deploy everything inside the Docker container, either with source code or with compiled libraries or anything else, but at least you know you have full control over what you place inside.

The container size can be a problem in some production environments. There exist layered containers, to re-use parts among multiple containers, but that just returns the dependency problem, right?

Containerization is an amazing software technology that can solve many deployment difficulties, but I'd like you to balance it against other deployment options and take the production environment restrictions in mind.

Integrating and interfacing

Once you figured out what "artifact" you will send to your production environment, you will also have to consider how that artifact will operate there. In other words, what happens after deployment?

This is mostly a matter of communication. You have to decide on a communication mechanism, a data format and the contents of the data. You'll also have to think about how to handle and communicate errors and other exceptional aspects.

The simplest common approach in today's webservice era is to deploy a Docker container, turn it into a REST server (that's a communication mechanism using HTTP), then send JSON strings or ProtoBuf objects (the data format). If it's a computational backend service, say some fitting algorithm, then you can put vectors inside the JSON and maybe some settings (that's the content of the data).

But there are many more options, all depending on the restrictions of your production environment. This probably deserves a separate blog post.

Deploy anything with Julia

Want more detailed information and tutorials?

Build entire Julia web apps? See the Genie framework.

Roll your own simple REST server? See HTTP.jl (used by Genie.jl).

Deploy Julia bare-metal on Arduino? Blog here.

Embed Julia libraries into C/C++ systems? Tutorial here.

Make a standalone app? See PackageCompiler docs.

Just want to share a script? Good, but make it reproducible!

I probably missed many others, feel free to add more links in the comments.

Conclusion

As I grow older and gain experience in deploying in more and more environments, I admit I appreciate fully statically compiled languages more. Plain-old C or Rust. You know you will be able to deploy anywhere if needed. Of course, you may not have such restrictions in your current production environment, but it's nice to work with a technology where you know you will not be blocked when the time comes.

However, such technologies are often tedious to use for scientific exploration or data analysis. Immediately from the beginning they add a lot of restrictions to your software development. Why can't there be a language that does it all? Where you slowly add the necessary restrictions as you progress in your project. I'm hoping we can tune Julia further in that direction, so that we have a language that's easy to write, performant when needed AND easy to deploy anywhere.

I hope this article helps to explain the concepts involved in deploying algorithms (or any type of code) in production environments. Understanding those concepts at the start of your project will make the entire process much smoother. It's essential to consider all dependencies and choose the right deployment method based on the production environment and the language you're using.